While researching history for some of the articles here at New Bedford Guide, I browse through a substantially large number of photographs. While a fair amount of them are uninteresting or dull, it’s not uncommon to come across some rather curious ones. In some cases, it takes an entire photo album to tell a story – in other cases, one photograph tells a number of stories!

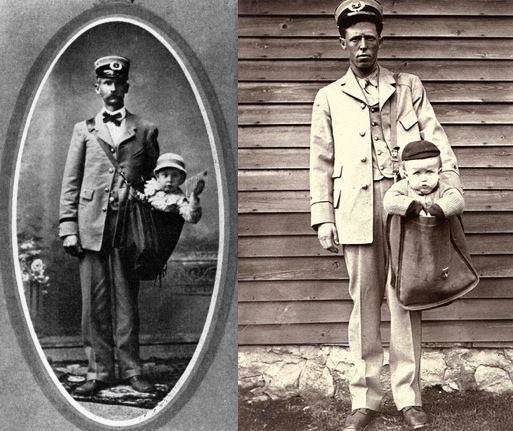

Such is the case when I came across the above photo of what appears to be two postal workers delivering an infant and and a baby. This is one that I just had to share. Before we get too far and draw too much attention from those who like to leap out of the woodwork and declare “FAKE!”, let’s clarify one thing: these two photos (assembled into one image) are staged photographs from the Smithsonian Institute’s collection.

However, this did happen. Let me explain. Let’s take a fun, little detour from the typical historic articles.

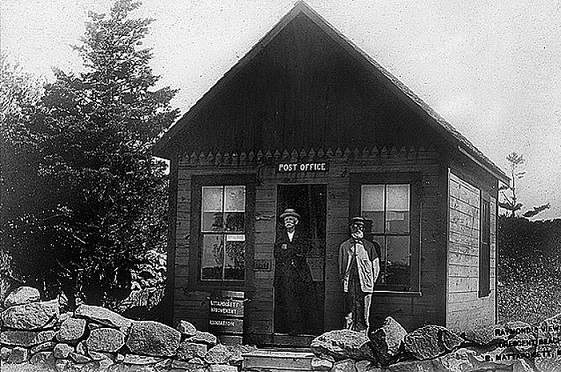

While the photographs were staged, they serve as hyperbolic images of actual historic events. The United States Postal Service’s precursor was called the United States Post Office, which was started in 1775 before the nation had official status. Its first Postmaster General was a fellow you may have heard of: Benjamin Franklin.

Before the “First American” headed the Post Office, there were a few attempts to get some sort of service running in the 1630s for a route from Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony to England. As colonies began to spring up throughout the 17th century, it was an organic part of the process to have routes connecting them.

In 1792, the United States Post Office was renamed to the United States Postal Service and the nation now officially had a legitimate delivery system in place that was government structured and run. In 1847, the postage was developed as a way to generate revenue for expansion and the increasing number of employees on the payroll. It cost .05 cents to send a letter up to 300 miles, .10 cents for anything over 300 miles. In the 1860s, massive growth in the rail industry led to expanded routes for the USPS and the rates reached a relative high of .06 cents in 1863.

However, by 1883 – two decades later – the rates would drop to .02 cents. While the USPS did have a Parcel Post system in place, it was only overseas to Europe. In 1913, Postmaster General Hitchcock aggressively sought to generate additional revenue for the department and felt that adding a domestic parcel post would do just that. He extended the service to domestic locations for the inexpensive rate of .02 cents plus an additional .02 cents per ounce over the first.

This service and rate meant that people now had access to goods that they couldn’t find in their locale. Local and national economies benefited greatly from the service and it actually stimulated that national economy. This rate was so affordable that there are anecdotes of university students mailing their dirty laundry, since it was cheaper to mail than actually launder. In fact, people sent all sorts of things through the post – butter, eggs, groceries and even day old chicks and chickens!

Sending poultry and the publishing of an article in the New York Times that Hitchcock was entertaining the idea of delivering children as parcel post, gave a number of people a bright idea: since it was more expensive to travel by rail or coach, why not mail them?! Since the Post Office hadn’t yet had precedence for sending humans through the post, they charged the going rate for mailing chickens: .53 cents.

Within weeks mail parents Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Beagle of Glen Este, Ohio got the bright idea to send their baby – who was just under the 11lb limit – to his grandmother, a Mrs. Louis Beagle a mile down the road. Carrier Vernon O. Lytle gladly obliged and delivered (pardon the pun) the baby safe and sound. Since it was only a mile down the road, the Beagles got the discounted rate of .15 cents…with insurance of course.

Later, in a similar story, a grandmother in Stratford, Oklahoma, sent a two-year old child to his aunt in Wellington, Kansas. As the New York Times reports: “The boy wore a tag about his neck showing it had cost 18 cents to send him through the mails. He was transported 25 miles by rural route before reaching the railroad. He rode with the mail clerks, shared his lunch with them and arrived here in good condition.”

The third officially reported incident (there were plenty of others) is when parents of Charlotte May Pierstorff sent their daughter from Grangeville, Idaho to her grandparents in another part of the state. There is also mention of a 9-year-old girl, who entered the main Washington City Post Office and asked that she be sent to Kentucky, however she was denied.

The mailing of Charlotte May Pierstorff was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. Postmaster General Hitchcock added regulations prohibiting the “mailing” of any human through the post.

On a rather large discussion thread on Facebook about this image, a number of people have made jokes about how they would have mailed their pesky sibling to North Korea or the Antarctica. It was advised that one remember to put the wrong return address lest the “package” be refused!

In essence, the mailing of children was never an official policy of the USPS. It was a sign of the times that people even considered the notion and it was really more of asking the postal worker for a favor because “he was going that way anyhow.” It wasn’t that there weren’t perverts or horrible things happening to children back then, but that people were more trusting, and perhaps a bit naive. Certainly people felt that one could trust a federal employee, anyhow.

On the aforementioned thread, a number of people shared stories of when they were children in the 1910s and 1920s. Here are two that stood out.

“I am 81 and me and my cousin were sent to Gramma by the milk train. We shared our lunch with the guys in the caboose and we had a great time. We were told they would look out for us and they did. It was a great adventure for this farm girl. Grampa worked for the railroad when he was a young man. We also rode the train when we were teenangers and went to Detroit from Nebraska to be in our cousin’s wedding. You couldn’t do that now. I remember the scene we did at Lincoln. We played the movie scene, kissing the boys goodbye, waving from the train as the boys ran throwing us kisses.B y the way these boys we knew and went along with the gag.”

“My father’s cousin was mailed by her father in Montana to his parents in western Indiana after the death of her mother from the 1918 flu epidemic, which also killed her aunt and baby cousin in Indiana. My Dad said she arrived safely, albeit dirty from coal dust from the train, and in possession of substantial funds much given her by other passengers. This was approximately 1920.

Her father was a mine worker in Butte and couldn’t take care of her. Children fly between parents today with airline staff as escorts I think. When children were mailed, they were looked after by the person responsible for the rest of the mail. They had money given by the sender and ate in the dining car or had food packed with them.

Kidnappers and other predators were not as prevalent then, and people in general looked out for each other. The young girl was 5 at the time, raised by her grandparents who also raised my Dad and his brother after the death of their mother. She grew up to become a wife, mother of four, and grandmother. She passed away 10 years ago. This has always been an interesting part of my family history. AND may you all escape this year’s flu safely!”

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA