British Colonialization of the New World; Origins of Dartmouth’s Earliest Villages

With the town of Dartmouth celebrating its 350th anniversary, there is a renewed interest in the town’s origin, history, and personages. There is a sense of awe attached to pondering how long three and half centuries is. While many parts of the world, particularly Europe and Asia, would consider 350 years to be a relatively short period of time – in the context of a nation that is officially 238 years old, it is a indeed a long time.

Unofficially speaking, there were a number of European – mostly Spanish – settlements that could be said to be firsts. San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1521. A little known place called San Miguel de Gualdape in Georgia which lasted for a whopping 3 months in 1527; a few decades after Christopher Columbus made his landing. Childersburg, Alabama is noted as the “Oldest City in the Continental U.S.,” since it was inhabited by Spain’s larger-than-life conquistador Hernando de Soto in 1540…for a month.

Most people who are history buffs, will leap at the chance to share the factoid that San Agustín or as we know it today: St. Agustine, Florida, is the oldest continuously occupied European-established settlement in the continental United States. She was founded for Spain by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in 1565, an astonishing 449 years ago.

However, all of these “firsts” were really firsts for Spain, and in a sense failures for that nation’s colonial expansion – for they would eventually become British territories. These satellite settlements initially were intended to establish trade connections or a foothold to spread religion and the Spanish had modest success in these ventures. The British had a primarily financial motivation for the colonization of the Americas.

Of course, this does not include the Brownist English Dissenters who are considered the first “British” to settle in the New World. The Leiden group’s motivation was to find a place where they were free to practice their particular brand of religion and perhaps generate enough industry to survive.

The same could generally be said about the Puritans and Quakers who followed. All three of these groups had one thing in common: “Chop wood, carry water.” They were all industrious, hard working individuals who saw the practical benefits of maintaining a trade connection with the nation they abandoned. They knew they could not survive without some sort of established economy.

While one cannot say that America today is a British nation, it is upon British colonial expansion that the America that exists today was built. In that context the first English settlement was established in 1585; the infamous Roanoke Colony of Virginia, which was in what is today North Carolina. Croatoa, Mothman, vanished, yada, yada, yada.

Once Jamestown, Virginia was settled in 1607, this oldest colony of the original 13 colonies was a sort of death knell for Spanish expansion in North America. A combination of failed settlements, competition from other European nations, and the allure of gold contributed to Spain’s decision to focus their interests on the Central America, South America and North America’s Southwest.

With Spain’s focus elsewhere, Britain seized the opportunity to further its interests in North America and began to pour vast resources into expansion. With a smaller Spanish presence, there was one less danger to worry about – although there was of course still the French to deal with.

The vacuum left by Spain was another factor in drawing the Leiden group congregants to the New World where Plymouth Colony was established in 1620. The same folks led by William Bradford – many of whom were aboard the Mayflower, Elizabeth or Anne – were involved in the famed purchase in 1650 of a tract of land that would become Olde Dartmouth. Surely Wampanoag chiefs Massasoit and Wamsutta, had no idea what this tract of land would become when they sold it.

Named after the town of Dartmouth, Devon, England, this tract of land would soon enough be sold to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). At this time it encompassed Acushnet, Fairhaven, New Bedford, and Westport. The various and somewhat confusing annexations to follow are readily available and common knowledge. Suffice it to say that it was incorporated in 1664, and was primarily an agriculturally based town.

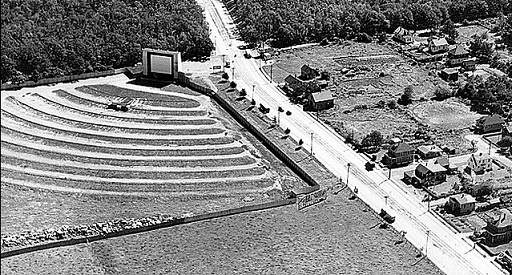

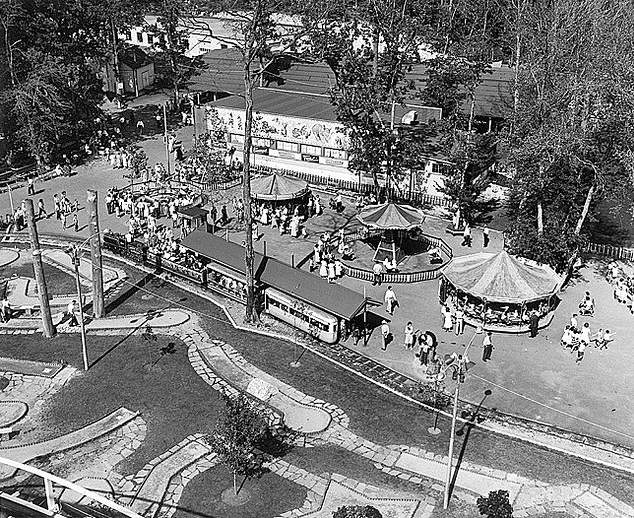

Once New Bedford’s wealthy whaling, textile and glass moguls discovered the natural beauty of the town, they began to build their stately homes and visit seaside resorts. Population has steadily increased since the 1920s drawing people for the same reasons!

Old Dartmouth at one point – before all its annexations – had twenty villages with no central government or town center. In essence, churches/chapels, the Meeting Houses and their Elders would serve in this capacity. Anyhow, without further ado…

Bakerville

The village of Bakerville got its name from the Baker family who emigrated from Cape Cod. The first Baker to arrive in the New World was Francis Baker from Hertfordshire who came over in 1635. The family nestled in at Yarmouth, Dennis and Harwich and remained there for five generations.

In 1806, six brothers born of Shubal Baker and Lydia Stuart moved to Dartmouth and settled on a massive tract of land. No surprise since they had eleven children (that survived). Surely, things got a little claustrophobic. Seven of these eleven were sons: Archelus, Shubal, Ezra, Michael, Ensign, Sylvanus, and Halsey. I’m unsure who the seventh son that decided not to relocate to Dartmouth was.

These 6 Baker farms were the origins of the name “Bakerville.” After they paved the way, so to speak, they were followed by the Brownells, Slocums, Shermans, Smiths, Briggs and Davis’.

Bay View

What little I could find on this village is that it was at the North end of Smith’s Neck. James Akin’s homestead included this village in its entirety and Thomas Getchell’s homestead was sandwiched between “Bay View village and Nonquitt.” While there is sadly little mentioned historically about this village, not much imagination is needed to figure out the origin of its name.

Bliss Corner

Bliss Corner is a 2 square mile water-less tract of land…if you don’t include coastline. I’d love to tell you some fantastic story about how an early settler saw the gorgeous flora and fauna and fell into a blissful swoon – hence its name. However, its origin is more modest in nature. Bliss is a surname of a family that contributed much to Dartmouth’s growth early on.

The Bliss family were Seventh Day Baptists from Rhode Island whose arrival in the region the mid-1700s was signaled by Reverend William Bliss. One of his sons, Arnold who was from Middleton, Rhode Island followed his father’s footsteps to Dartmouth and in his career choice: he was also a Seventh Day Baptist preacher. Like many they owned portions of land, did some farming and ran a saw mill; most notable was another of William’s sons John Bliss, who was not only a preacher, this time for the Freewill Baptist Church, but also served in the Revolutionary War under Col. Archibald Crary. With the birth of Arnold’s son William (grandson of the original William) the family would begin to leave the clergy and focus on milling and farming.

Regardless, they contributed in a multitude of ways to Dartmouth’s industry, community and society and rightfully earned the right to have a very special part of Olde Dartmouth named after them. On a side note, the Bliss family’s religious contribution and presence still exists in Rhode Island today and there is a Bliss Four Corners and Bliss Four Corners Congregational Church in Tiverton.

Hixville

Founded in 1785, Hixville, or Hicksville has similar origins in that a surname contributed to its moniker. The surname is one of the country’s oldest and arrived with Samuel Hicks, Sr. who came aboard the Anne in 1623. Samuel Hicks Sr. was one of the town’s original founders or proprietors and settled in to put Dartmouth on the map when he moved here in 1666. In all likelihood a Quaker, Samuel produced quite the number of progeny.

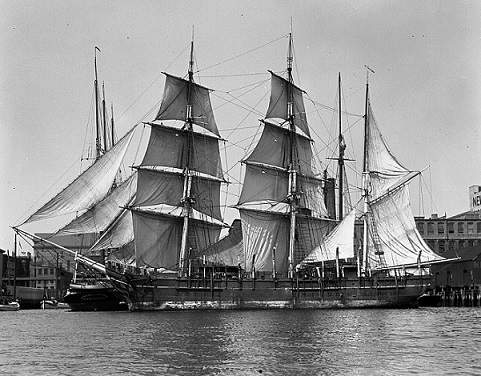

In this case, the Hicks family had more business-minded leanings as opposed to the religious oriented Blisses. Most of the Hicks had business ventures in booming nearby New Bedford, including Kirby & Hicks Stable on the corner of Elm and Pleasant Streets, Herbert E. Hicks Antiques, at 38 North Water Street (a shop which curiously used the stern board of the whaling bark “Atlantic” in its storefront), and the whaling vessel “Andrew Hicks.”

There are few families who left a more indelible mark on Dartmouth and beyond, than the Hicks family. Indeed, their presence was so powerful that there is still a Hick’s Street in downtown New Bedford today, sandwiched between Logan and Washburn Streets, east of Route 18.

Nonquitt

Nonquitt is a corruption of the Amerindian word Namquid or Nomquid, and actually has no meaning. In the 17th century this area was settled by Nathaniel Howland and was called Nomquid Neck. Originally this referred to the east side of Smith’s Neck. By 1872, it referred to a much larger area that became a seaside community the we know today. These terms were applied differently and refer to different stretched of land depending on what time period you are discussing.

Padanaram

Padanaram Village rose from the remains at the foot of Lucy Street, of a settlement burnt to the ground during King Philip’s War (1675-1678). Padanaram was a village before it was dubbed so. It was a shipbuilding mecca called Ponagansett (and later South Dartmouth Village) leading up to the Revolutionary War when a few local Tories that were banished, returned with a small band of Redcoats. These rogues and knaves made an attempt to raze the village as best they could, but were interrupted by a spirited unknown lady who not only doused the burning homes, but made sure to spare a generous amount for the Tories and Redcoats themselves! They managed to burn down two homes, but her spitfire – pardon the pun – salvaged a third building: St. Peter’s Episcopal Church on Elm Street. Girl power!

After the war, Ponagansett became a supporting village for the Whaling Boom in New Bedford. Many industries benefited by supporting whaling, even those altogether unrelated. One of these, the salt industry, made a fizzle. Many businessmen made an honest go of it, but for naught. Why mention the salt works? Because one of those businessmen, was Laban Thatcher, who was a sort of early Panagakos. He invested in a number of properties and built, owned and ran windmills, a magnesia factory, shipyard, wharf and more.

In spite of his successes, his salt work was dubbed “Laban’s Folly” by the community, since it utterly fell flat.

Regardless, it would be Mr. Thatcher that would dub the village Padanaram. Contrary to what many believe or what is the common method of place naming in New England, Padanaram is not an Amerindian word, but Aramaic, meaning “the fields of Aram.” Of religious bent, Thatcher felt there were uncanny similarities between his life and the Genesis’ Laban, who lived in the plains of Padan-aram.

Russells Mills

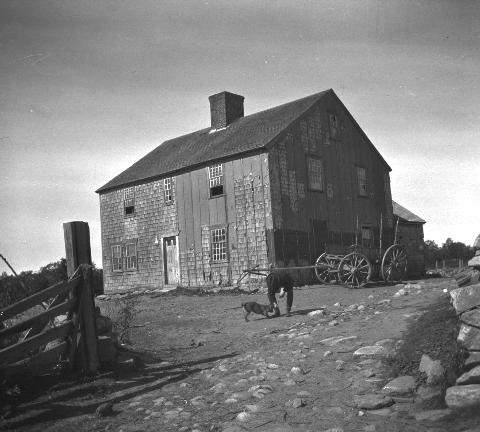

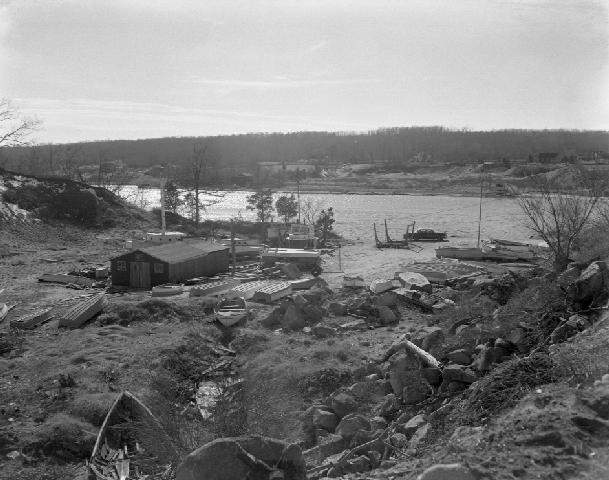

The oldest of all Dartmouth’s villages had its beginnings in the early 17th century. The first place settlers look for when they arrive is water. It’s not only necessary to sustain life, but needed for washing, power or energy, milling, smithing and diverse other tasks. The Slocum or Paskamansett supplied this amply. Like the first two villages we mentioned, Russells Mills was also named after a family: the Russells, of which a vast amount of literature has been written by people far more capable and talented. I refer you to them.

Of interest is where the “mills” part of Russells Mills is derived. Many historians have pontificated, guessed, and theorized which type of mills these may have been. Unfortunately, since they were built prior to King Philip’s War and important parts of the infrastructure, when Metacomet and crew came rolling around they were prime targets. Historical records that may have told us what the first mills were, surely went up in flames with the rest of the area. What historians are sure of is that it was not an iron mill.

Residents returned and rebuilt at the advent of the war, and thankfully it remains relatively unchanged – retaining the early character of the village.

Smiths Mills

Originally called Newtown, the very first act of the town of Dartmouth after its incorporation was to offer 1/34th of the total land of the town to anyone that would immediately erect a mill here.

On June 30, 1664, Henry Tucker and George Babcock took up the task. History does not record the specific sort of mill that was erected and as aforementioned King Philip did a bang-up job destroying the town and historical documents. The first mention of a mill in Smiths Mills is George Babcock’s mortgage of a grist mill and a fulling mill in 1702.

In 1706 an Elishib Smith acquired the land, farm and mills and even erected a saw mill of his own.

The name “Smiths Mills” is missing an apostrophe denoting ownership, i.e. “Smith’s Mills,” or “Smiths’ Mills.” Were the mills named after an early family or individual that settled there, e.g. Samuel Smith, town surveyor or Judah Smith the very first settler there? Or was it named so because there were a number of various smithies there? I couldn’t find anything suggesting either, however I find it likely that the latter is the case.

Smith’s Neck

Smith’s Neck was originally called Namquid Neck which means “The Fishing Rock Place.” The particular Smith that Smith’s Neck is named after is a one John Smith, a boundboy (a young indentured servant) of the Mayflower’s Edward Doty. With Doty’s leave he took to the sea and eventually was commissioned aboard a barque that served as one of the earliest versions of a Navy.

In spite of the fact that John Smith had very humble beginnings he earned himself enough to purchase a home in “Plimoth Colonie” which he exchanged for land in Ponagansett. After removing to Dartmouth, he built himself another home and began to rise in prominence as an local arbiter and town surveyor. He earned the title of “Lieftenant” and was nicknamed “The Lad of the Mayflower” by locals.

John would marry twice – once into the Howland family (Deborah) and a second time to a Ruhamah Kirby. He would have thirteen children and many of them would marry into the prominent Russell and Howland families.

While not true villages, or even hamlets there were tiny areas that were in essence neighborhoods consisting of homesteads. Places like Allen’s Neck, Colvin’s or Durfee’s Neck, Gidleytown, Mischaum Point, Perry’s Grove, Round Hill, Salt-House or Salter’s Point, Slocum’s Neck, etc. weren’t true villages, but worth mention.

Dartmouth should be rather proud of its history, for it really is America’s history and Dartmouth’s 350th anniversary is just as much an anniversary for America!

ngg_shortcode_0_placeholder