New Bedford Streets; A Piece of Americana: Tarkiln Hill Road

Welcome to next installment in the New Bedford Streets; A Piece of Americana series. Previously we covered William Street, Kempton Street, Middle Street, Centre Street, Ashley Boulevard, Elm Street, Coggeshall Street, Mechanics Lane, Washburn Street and others. If you would like to read those or perhaps revisit them, they can be found by using the search bar to the right. You can also select the “Streets” category.

As usual, I’d like to re-iterate the importance of reader feedback, correction, and contributions. In the process of exploring these streets, I try to confirm or validate statements and dates by finding multiple sources. Unfortunately, if all those sources are making their statement based on an older, incorrect source, and there isn’t any dissenting information available, there’s no way to know otherwise. So by all means, please join in.

In addition, when trying to validate some statements, often there is very little to no information available. I haven’t decided which is worse – finding one source, or finding multiple sources, but not knowing if they were all founded on an inaccuracy. So help from local historians, those who remember, oral histories and anecdotes handed down through the generations, people with private collections, and even know-it-alls will help!

By all means, let us make this an open discussion to keep the “wiki” accurate.

______________________________________________________________________________________

We New Englanders are famous for the pronunciation of our streets, towns, and cities. Laughs abound whenever an out-of-town friend or family member visits and discussions about the region are had. There is a very popular video where a number of Americans from other regions in the U.S. are given a card with a local city or town on it, e.g. Worcester, Billerica, Gloucester, Leominster, etc. Very few people, if at all, get the pronunciations “right.”

American English prefers practicality over aesthetics. We’d rather use short vowels than long, use contractions rather than pronounce out both words, and use nicknames rather then full names. We have things to do, places to go, and we’re heading to work!

So in this spirit, we prefer to gloss over a few letters to speed things up. Hey, if we want to make a “k,” “g,” “e,” “t,” or other letter silent, it’s our prerogative! We do it to words like knight, buffet, Worcester and even New Bedford (no “r”.)

So it should come as no surprise that Tarkiln Hill Road becomes “Tahkin Hill Road.” Goodbye “r” and “l.” We ain’t got time ‘fo dat. We have Titleist deals to sign and a need to get to Dunkin’ Donuts stat. Outta my way.

Tarkiln Hill Road is one of the oldest roads in the region, rich in history. It’s a road I drive daily. Etymologically speaking, this compound word can be broken down to “tar” and “kiln.” While we all know what tar is, fewer of us know what a kiln is. It’s a word that is rarely used in daily conversation and most would say “It’s an oven of sorts.” You would be very right – the word is derived from the Latin culina which we see is where we get culinary from. The Old English spelling was cyln.

So what we have here is a hill where a cooking stove for tar is, right? Well, sure. In lay terms that is exactly what we have here, but this “tar kiln” refers to something very specific.

Most people think of paved roads or streets when they hear the word “tar,” but from the Iron Age onward much of the world has been using tar for a multitude of reasons. Europeans turned it into an industry and commodity and of course American colonists were quick to utilize it. Tar was used for preserving and water-sealing/repellent on wooden sailing vessels, leather clothing, sails and roofs. It kept out the ocean water, rain or rot.

Unknown to many is that it was also used as a general disinfectant, to flavor candies or amazingly as a panacea or medicine for those mortally wounded. Today it is still used in dandruff shampoos, in cosmetics, paint and of course, preserving wood surfaces.

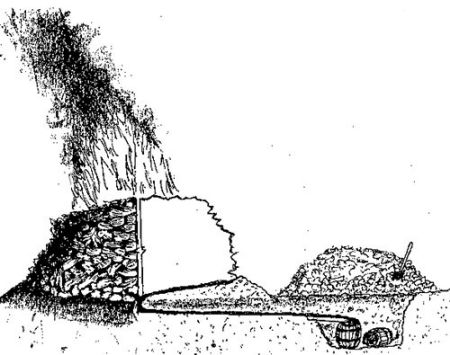

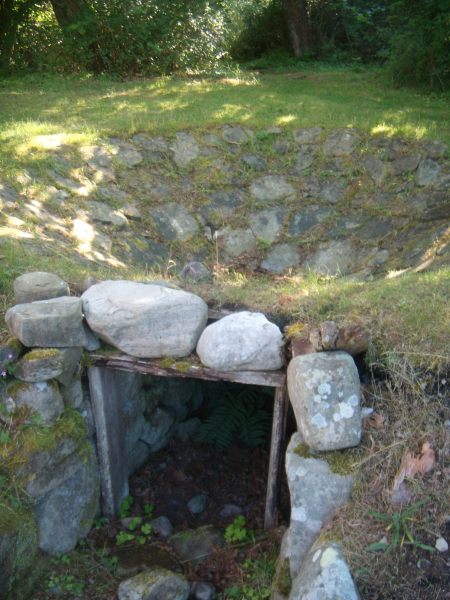

Where does the kiln come in? Tar is a product of burning wood – primarily pine, hence the term pitch pine or candlewood – for hours or even days in a closed environment. The fire would burn far past the point that the wood became charcoal. You need a kiln for that – often made from limestone and where that wasn’t available a deep pit was dug. There was a slight gradient to the kiln, so that the liquid tar could ooze out and be collected.

An integral aspect to the process is the minimizing of oxygen, but maintenance of the heat. This is achieved by covering the charcoal in moss and/or dirt. For days the tar would be collected. If you are a history buff or farmer, you know that nothing was ever wasted in colonial times. Once all the tar was extracted, the dirt and moss would be swept aside and the charcoal and by-product of tar kilns – turpentine and pitch – would be also collected.

Tar, pitch, turpentine and charcoal all became commodities to export back “home” in England. Since the colonists were perpetually clearing forests to build towns, homesteads and farmsteads these commodities were in abundance. In fact, it become an industry that burgeoned so much that towns began to complain about the odor and constant smoke from the glut of tar kilns. Some states like New Hampshire even allowed residents to pay in tar instead of currency. In the 17th century Massachusetts tried to stem the destructive industry by putting caps on the amount of barrels that could be produced annually.

Eventually lumber and ice harvesting come onto the scene and many jumped ship, pardon the pun. However, it did undergo a short lived revival in the early part of the 20th century.

So we’ve clarified what a tar kiln was and how our forebears in the region utilized it in a typically New England industrious way. So why in tarnation – again, pardon the pun – was this road specifically called Tarkiln Hill Road? This stretch of road is Main Street in Acushnet, becomes Tarkiln Hill Road once you cross “the river” and turns into King’s Highway once it hits Route 18. Coincidentally, nearby Pine Grove Cemetery was originally known as Tarkiln Hill Burial Ground prior to 1853 – before the city owned it.

This road was already a common Amerindian Path before settlers arrived. After Olde Dartmouth was purchased in the early 1650s it was referred to as “Old Rhode Island Way” in many historical documents. Reason being that the trail was used to travel between Plymouth and Newport by the first peoples. Within a few decades the Loyalists would pay tribute to the King back in England by dubbing a section of the trail “King’s Highway.” That King was likely James II or Charles II; you may know better than I do – chime in.

There are no historical documents I came across – I pored through scores of them – that mentioned a specific tar kiln. It is very probable that it was used to refer to multiple tar kilns as if to say “The hill with all the tar kilns on it.” The same way we would say “Dog Park” or “Auto Mile.” The fact that it does not have a surname attached to it lends credence to this idea – ponds, mills, and other landmarks would have surnames attached, e.g. Smith’s Mills, Turner’s Pond.

Considering that there was a tar industry boom and and a plethora of tar kilns in the area it would be reasonable to assume that there were a number of tar kilns on the edges of forests. It is also likely that tar kilns were temporary and shifted as trees were harvested. This explains the lack of a name attributed to the tar kilns.

Since the further back in time we go the fewer documents were kept it likely means that the tar kilns in the area go way back to the earliest times, perhaps even as far back to the first settlers. Since the street was an Indian path when the very first settlers arrived and mentioned by the Dartmouth Proprietors it would be safe to say that Tarkiln Hill Road had its first tar kilns between 1655-1680. This would make a lot of sense considering England was virtually deforested by the early 1700s and would have relied on the colonists exporting as much of it as possible.

We’ve gone from Indian path to Old Rhode Island Way to Tarkiln Hill Road and the street being truncated by town and city lines. Next time you drive on Tarkiln Hill Road you can say “I know what the name of this street means and why it was named so.” By knowing the backgrounds of the streets in this series we are getting to know the region’s – even our nation’s – history a lot better.

It’s a way to pay tribute to the hard work and industrious nature of our forebears that made our first world lives possible today.