New Bedford Streets; A Piece of Americana: County Street

Welcome to next installment in the New Bedford Streets; A Piece of Americana series. Previously we covered William Street, Kempton Street, Middle Street, Centre Street, Ashley Boulevard, Elm Street, Coggeshall Street, Mechanics Lane, Washburn Street and others. If you would like to read those or perhaps revisit them, they can be found by using the search bar to the right. You can also select the “Streets” category.

As usual, I’d like to reiterate the importance of reader feedback, correction, and contributions. In the process of exploring these streets, I try to confirm or validate statements and dates by finding multiple sources. Unfortunately, if all those sources are making their statement based on an older, incorrect source, and there isn’t any dissenting information available, there’s no way to know otherwise. So by all means, please join in.

In addition, when trying to validate some statements, often there is very little to no information available. I haven’t decided which is worse – finding one source, or finding multiple sources, but not knowing if they were all founded on an inaccuracy. So help from local historians, those who remember, oral histories and anecdotes handed down through the generations, people with private collections, and even know-it-alls will help!

By all means, let us make this an open discussion to keep the “wiki” accurate.

__________________________________________

Some streets in the city are of the nature that you are on them so much that they are just a part of proverbial “furniture.” Just another part of daily life that you pass by and don’t pay any attention. County Street is one of those streets that we often drive down, but really never give much thought.

Of course, why should we? Why should we pay any mind to a street name, how it got its name or its meaning? Well, maybe you are a history buff or nerd, like me. Maybe, also like me, you love New Bedford and want to glimpse into the idea of “What’s in a name?” A name has power and is a doorway to all the knowledge and happenings associated with it.

So, let’s open that door.

The first historical mention of County Street that I could find was from 1675. At that time conflict between settlers and Amerindians was at an all-time high and King Philip’s War was in full swing. Villages, towns, farms, homes, and lives were destroyed on both sides – both for their futures, but one in the name of “progress,” the other for their very existence. It was said that most of Fairhaven, Dartmouth, Westport, Acushnet, and swaths of New Bedford were completely destroyed and the remaining homes were secluded ones set at a distance.

Those settlers survived either did so by fleeing into the woods, local garrisons to ride out the hostilities or to some of the fortified homes of the “well-to-do.” Courts in Plymouth decreed that Olde Dartmouth residents would have to rebuild as close to the garrisons as possible for their own safety. One such garrison was John Russell’s at “Ponagansett” which held Amerindians who had surrendered.

The famous Captain Benjamin Church sent troops to the region to serve as relief and to march captured Amerindians back to Plymouth – they did so by going through present day Dartmouth and New Bedford via the head of Clark’s Cove, and down County Street which was then called County Road.

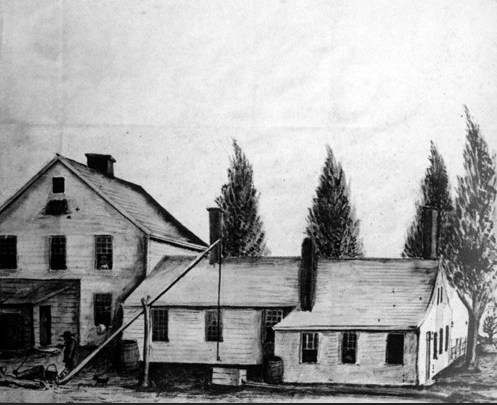

There really is not much of a mystery when it comes to the origins of the name. It was clearly a street that was part of a much larger delineation of the county’s borders. While hard to believe today, County Road was at the fringes of the then sparsely populated Bedford Village. As you head east from County Street and head towards the water, it was primarily large farmhouses with tracts of land between them. The main farmhouses were built on higher ground and thus along County Street itself.

During the Revolutionary War thousands of Redcoats landed at Clark’s Cove to do their worst to New Bedford. They went straight up Brock Avenue (appropriately called Middle Road at that time), hopped onto County Road and went to Main Street or Union Street. When they arrived, the village was mostly abandoned – the village artillery company had gone off to fight- so they torched, destroyed, pillaged and plundered everything – even the vessels that were docked at the piers.

At this point in County Road’s history, we reach a rather infamous event.

John Gilbert, who was a servant of New Bedford’s Joseph Russell lingered in the city to transport some of Russell’s household goods and wife to safety. When he arrived he found that Mrs. Russell had already left, but she had left a note for him to assist a Mrs. Akin – a lady from another well-to-do household.

While fleeing, both were intercepted by British soldiers, but Gilbert broke free…leaving Mrs. Akin behind, likely knowing that she wouldn’t be harmed by the soldiers. While fleeing he ran into two other city residents, William Hayden and Oliver Potter and together the three made their way to County Street, near North Street and hid behind some trees.

From their hidden vantage point, they fired on the British killing two and were able to get away. However, what they did was whack a hornet’s nest and impassioned the British to retaliate, which they did by firing upon the very first residents they came across. Unfortunately for Abram Russell, Thomas Cook, and Diah Tafford – citizens who were on their way out of the city – they were the first to be spotted.

The British fired upon the trio from a distance and then charged with sabers and bayonets. 20-year old Tafford was shot through the heart and died where he stood, but the enraged British continued to hack his lifeless body.

Cook was shot in the stomach and leg and left to die in the road, as was Russell. There they lied in the road bleeding and suffering through the night. When locals begin to filter back into the city in the morning, Cook and Russell were discovered still there. Cook had passed in the night and Russell died early that afternoon.

There is still a small memorial on County Street commemorating this event, but it is hidden and you have to look for it on foot.

The next mention of County Road is from 1795 and mentions that Bedford was still a small village with a population of approximately 1,000, only a handful of passable streets which ran off of County Road, no courthouse (but did have a Quaker lawyer), a school teacher or two, and even a doctor. At this time Union street was a simple cart path that ran to and from the water.

At this point, the New Bedford/Fairhaven bridge was a year away from being built. Imagine that? No bridge, no getting stuck on it, no traffic. The coming bridge -first of many incarnations – was a simple one, so they meant it didn’t turn or lift and that means it couldn’t break down.

In 1815 it was said that pretty much everything West of County Road was all forest. This is also the year of the “Great Storm” or what we would call a hurricane. The hurricane came during a high tide and created record flooding – 10′ above normal readings and the water went as high as Third Street. The New Bedford/Fairhaven bridge which had just been built was dashed to pieces as was the bridge in Acushnet at the head of the river. Many buildings were destroyed, ships pulled from the dock and moorings and smashed, and there was a tragic loss of life.

In the 1820s a circus came to the village and was a part of the regular entertainment for the locals for years. That took place on the corner of County and Elm Streets right across the street where McDonald’s is today. Selectmen thought of it as a form of debauchery and fought constantly against its existence – apparently, it went against their conservative Quaker values.

In 1830 New Bedford was growing exponentially, the Portuguese started arriving to look for whaling and whaling related jobs. County Road was handling most of the city’s main traffic and was designated a street. It grew up.

The William Rotch, Jr. House, now called the Rotch-Jones-Duff House and Garden Museum was built in 1834 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.

In 1836, the aforementioned circus on County and Elm Streets was replaced with “The Lions Theater,” but the city’s Quaker officials didn’t think it any better than the circus. We can’t be having people sinning by watching a little Shakespeare.

Lest you think this was limited to some cranky, uptight officials: when the city had a vote on whether the theater would be allowed to have a license and continue as a busines, the results were 12 “Yeas” and 566 “Nays.”

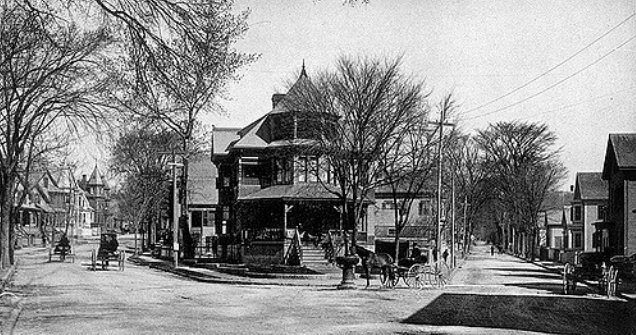

In the 1840s, County and Wing Streets were known as “Dog Corner” where “…daily and nightly constant exhibitions of drunkenness, brawling and profanity; and at dusk such is the concourse assembled there that it is not only disgusting and indecent, but such is the character of the assemblage, that it is dangerous for civil persons to pass in the vicinity.” Can you think of any similar spots like this today?

In the 1860s, the Wamsutta Club – which did quite a bit of bouncing about – made its home on County Street. 1892 was, of course, the year Lizzie Borden would be prosecuted by a New Bedford lawyer for her crimes. The trial was held at the Superior Court House on Court and County Streets.

In 1909 New Bedford’s first high school would be erected right on the site where our earlier player, Joseph Russell, had his home. Though by 1909, it was Charles W. Morgan’s estate. In 1963 Channel 6 began broadcasting from a studio on County Street and their call letters would be WTEV until 1980 when it became as most remember, WLNE. Remember Bozo the Clown, Dialing For Dollars, Creature Double Feature, Kung-Fu Theater and other childhood shows?

The street would be placed on the National Historic Register during the nation’s bicentennial in 1976. And the rest, as they say, is history…

Do you remember an old business that used to be on County Street? Have memories of an event in the city’s history? Know of an historical piece of information you want to share that is related to County Street? Comment on this article to share with the community.