Every schoolboy learns about how America “won the war” against, as well as our independence from, Britain in the 18th century. As often happens in history, events are summarized into neat, tidy little packages – an assumption with the advent of the Revolutionary War is that England packed up their belongings and went back to their homeland with their tails tucked between their legs.

What many don’t know – or don’t recall from their school days – is that England still maintained their presence as the colonial “big brother.” They didn’t simply tuck tail and leave, they stuck around to be royal pains in the arse – pardon the pun. There was too much money associated with the upstart colony to completely sever the “paternal” relationship.

Those who were paying attention (or have good recall) will remember that tension between the United States and Britain continued to rise until it culminated in a full blown conflict, the War of 1812.

Until the “Second War of Independence” – how some referred to the War of 1812 – the British maintained an attitude of hostility and downright hostility and downright belligerence. Sour grapes, I say.

There were many ways in which England would be antagonistic to America and her citizens’ way of life. One of the these ways was to financially assist Amerindians in their rightful campaign to restore their own sovereignty – England would encourage the Natives to fight for the Northwest Territory which England ceded to America in the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The idea was to stall the American pursuit of further expansion across the continent, thereby compromising their ability to consolidate power through annexation of more territory or states. Remember this was a time when America was still comprised of the original thirteen colonies – England still had interest in French America, as well as, Spanish America.

Another major way that England would create problems for the 13 Colonies was to hurt them in the wallet by harassing trade routes, particularly across the Atlantic. England was the most powerful naval force in the world – if they couldn’t defeat America on their own land, surely they could batter them at sea.

Impressment might be another term you recall in your younger days at school – the act of taking men into captivity and forcing them into military or naval conscription – what we colloquially call “Shanghai-ing” or crimping. Every school child recalls the stories of unwitting patrons of a local tavern who would be amid libations and festivities only to wake up the next morning at sea. England was especially adept at this and virtually turned it into a commodity or trade. Some would say a past-time.

During the time period after the Revolutionary War and leading up the War of 1812, England was fond of impressing Americans and it wasn’t uncommon for Americans at British ports to be kidnapped and forced into service for the crown. It wasn’t that they were adverse to crimping their own citizens – they did their fair share of that – but targeting those pesky Americans would come with fewer immediate repercussions and would serve as a bit of revenge for the Crown. Long live the Queen, right?

New Bedford being a port city and one well-known for whaling, obviously had trade relationships with many nations. Often, this meant leaving New Bedford for years at a time and what is a sweeter target for impressionism than a whaling vessel full of sailors? One could lessen the learning curve for the “intern” and get some immediate production out of the staff.

There are many anecdotes and historic incidents of the conflict between the British press-gangs and American sailors, but one that strikes home because it involves locals from New Bedford and Fairhaven, is the capture of the New Bedford whaling bark, the Fanny, in April of 1810.

Built in 1807 at Hanover, MA, the 95-ton bark was 86′ long, 25′ wide with a depth of 12’6″ and mastered by New Bedford Captain, Elias Terry. Of particular note, is a 15-year old cabin boy from Fairhaven, called Joseph Bates. Other locals aboard were fellow Fairhaven-ites James O’Neill, Lemuel C. Wood and Charles Proctor. In addition, there were some notables – a Samuel Parker from Acushnet, a Henry Alden from Westport and Mr. Russell from New Bedford.

Joseph kept a diary and it is through him that we know of the account of the misadventures of the Fanny and its sailors, as it set sail for what they assumed would be a typical whaling voyage of years.

It was not uncommon for whalers to not return home for three or more years and while they, of course, would not be at sea the whole time, they would have to set anchor for provisions and respite – perhaps repairs – at a number of international ports.

It was in 1810, for unknown reasons, that Captain Terry decided to set course for Liverpool and he, the crew, and the Fanny docked in April of 1810. They were in Liverpool for only a few days when they encountered a press-gang – on the morning of April 27 they woke up to an officer and twelve men barging into the boarding house while the crew was enjoying some time off.

The gang demanded to see identification papers to determine where the sailors came from, their authorization and which protection, if any, they had. In spite of producing the proper documents and showing that none were not British nationals, they were seized and dragged through the streets like common criminals and tossed into the galleys.

The following morning, they were placed before a local magistrate and “sentenced” to service as conscripts of the Royal Navy and interned along with 60 other Americans – culled from other press gangs – aboard the “Princess.” Can you imagine what it would feel like to leave home to make a better life for your family by undertaking one of the most dangerous jobs on the planet, to only be “kidnapped” and made into a sailor for another government’s military? It gets worse.

Any sane person respecting liberty would take the first opportunity to escape enslavement and such conditions, which a fair number of the Fanny’s crew attempted to do a few months later. Here is the young Bates’ account of the experience:

“An attempt to regain their liberty by breaking the bars of the portholes and thus to escape by swimming ashore was met with severe punishment, the Americans being taken one after another and whipped on their naked backs in the most inhumane manner. In a few days he and others, pronounced in good condition, were transferred to the stationary or received ship, Saint Salvador Del Mondo, at Plymouth, where he found 1,500 other victims like himself. In three days he was drafted, with 150 others, and sent on board His Majesty’s 74-gun frigate, Rodney, Commodore Bolton.”

After nearly a year at sea, word of the impressment of greater New Bedford’s own reached home. Many of the families tried to bargain, barter and negotiate for the release of their loved ones to no avail. Thus was their lot until June 18, 1812 with the outbreak of the war between England and her 13 colonies for a second time.

While being impressed and forced into being a sailor is one thing, being told that you would have to take up arms and fight your fellow Americans is something that simply would not acceptable. Bates and five others absolutely refused to fight fellow Americans, stormed the quarterdeck and appealed to the commanding officer. “We understand sir, that war has commenced between Great Britain and the United States and we do not wish to be found fighting against our own country; therefore it is our wish to become prisoners of war!”

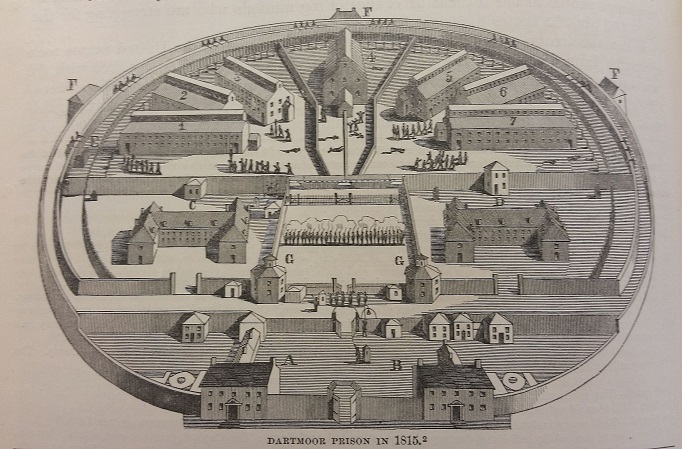

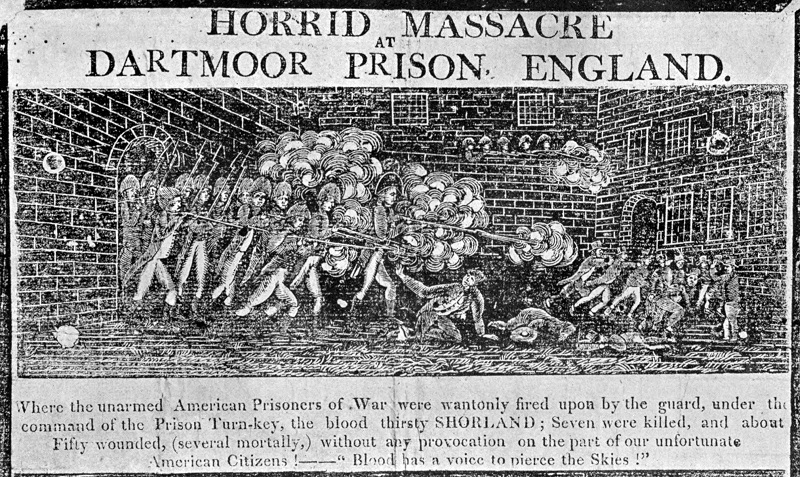

Rather than be traitors they would rather lose their relative freedom and be placed in shackles, pillory or hung. Their reward for this “mutiny” was ill treatment, hard labor and a reduction in their food rations until they arrived at their next port where they would be placed into custody and tossed into Dartmoor prison in the summer of 1814 with 6,000 other Americans. The sheer number of Americans just in Dartmoor alone illustrates how common impressment was and the Fanny’s experience was certainly not an uncommon one.

At one point the prisoners would become fed up with the sheer amount of forced labor they were undertaking, their loss of liberty, and desire to return to family and country, that they began to dig an underground tunnel long enough to get them safely beyond the prison walls. The long term plan entailed going from there to the seacoast where they could seize a vessel large enough to sail them to France.

All was going according to plan when a traitor in their midst – New Bedford’s first recorded snitch – plea bargained for freedom for “ratting.” I couldn’t find any historical accounts of who this fellow was or what “treatment” he received by his betrayed countrymen.

For our protagonists, after almost 6 years of “service” to the crown – 2 1/2 years of which were as prisoners at Dartmoor – relief would come in April of 1815 as negotiations were made between the two nations and the War of 1812 would come to a close, culminating with the Treaty of Ghent. While the treaty meant the war had ended, it didn’t mean the end of press-gangs and England’s policy of foreign impressment, fortunately for the Fanny’s crew it did.

A jubilant Bates explained “Shouts of rapturous joy rang through our gloomy dungeons such as most likely will never be heard there again. What! about to be liberated; go to our native country and gather around the paternal fireside once more! Yes, there is hope in us, and it seemed sometimes as though we were almost there.”

Yet, their story doesn’t end there. Even though our crew and other Americans – totaling about 300 – were set free and boarded the Mary Ann and set sail for home, drama would find them again. Anyone who was born in raised in New England knows that it is its own little pocket of culture, dialects, cuisine, customs, and ways of life. After being only days away from the New World, the crew found out that their destination was not home, but that they were heading for the James River in Virginia. They found this out as they approached Block Island.

So, like good Massholes they mutinied, stormed the helm and took over the ship. You can impress us, makes us subjects of the crown, even treat us poorly, but you will not force us to live down South! They managed to commandeer the vessel and set for the port of New London, Connecticut where they chartered a fishing smack and bee-lined for Boston.

Of course, with many Fairhaven-ites and sailors from the whaling city, before the vessel would reach Boston a pit-stop was made to New Bedford and Fairhaven to drop off locals.

“Here Mr. Bates met a friend and townsman of his father’s Capt. Thomas Nye, who lent him $20 and to buy some decent clothing. The next evening, June 15, 1815, he had the “…indescribable pleasure of being at my parental home in Fairhaven” surrounded by family after six years and three months absent from them.”

Thus ends our story about the voyage and misadventures of the bark Fanny and her crew. Impressment was quite common in those times, but frequency with which England impressed Americans got so out of control that it was one f the contributing causes for what is commonly called the War of our Second Independence, the War of 1812.

The Fanny would go on many more voyages before being trapped in ice and eventually crushed, during a whaling voyage.

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA

Very interesting as always!