With this new series of articles, we’re hoping to shed a little light on how things were done in the 19th century. A fun way to lend perspective to our modern way of living. We often hear “You don’t know how good you have it. When I was a kid…” or “You should clear your plate, there are starving kids in Cambodia/Ethiopia.” So this is an attempt to add images and detail to those perspectives – without the hyperbole.

Well, maybe a little bit.

When we peer back into the past and see how things were, we come to appreciate the things we have – perhaps taking them for granted a little less or no more. Of course, I will keep this is local as possible and share any anecdotes I come across in my historical research. While no one today was alive in the 19th century, this is a series on perspectives, so by all means share YOUR story on how things were in the era that you grew up in!

The inaugural article will begin with something we can’t live without and most of us genuinely take for granted. “I love having a refrigerator, it allows me to have refreshingly cold drinks, preserve my food for longer, and allow me to heat my leftovers the next day. Fridges are great!” said no one ever.

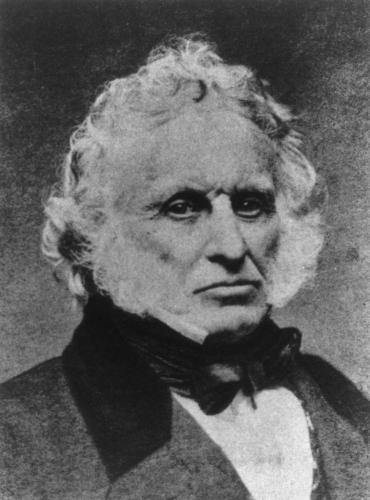

Frederic Tudor, the Ice King who started a multi-million dollar industry in the 19th century.

It is also one of those pieces of technology that most of us don’t understand how it works. What is the exact process that allows us a grand luxury? To have a device that we forget exists unless it’s humming in the middle of the night or we lose power? Well you can add that aspect to the list that includes cars (for most of us), radio, TV, microwaves, phones and many more.

Regardless, it’s not important to understand the exact process to appreciate it. The effect of refrigeration on civilization was and is a massive one. Speaking locally or domestically, waterways were the first thing explorers, conquistadors, and settlers looked for. A water source provided sustenance, energy, water for smithing and livestock, etc. Typically food would have to be eaten soon after it was captured.

Refrigeration allowed us to be able to move into isolated areas when it came to settling. One no longer had to live near a waterway to sustain living. One could stockpile enough food that live off of for days or weeks without need to head to the developing areas to re-supply or head back towards a waterway to fish or hunt.

The first known historical reference to refrigeration comes from ancient China’s Shih King period, who referred to “ice cellars.” Subsequently, refrigeration is mentioned in Jewish scripture, by the Egyptians, Greeks, Romans and the Indus Valley.

In the 19th century refrigeration was a booming industry, especially here in New England. In fact, ice harvesting as a commercial business had its start right here in New England. In the start of the 19th century, few people utilized refrigeration because there simply wasn’t a service in place. There were no storehouses to supply the ice, no supply chain, and no personnel to deliver it. It had isolated use by few individuals and certainly wasn’t commonplace.

Andreoly Ice House of New Bedford in 1920. (Spinner Publications)

How the ice harvesting industry got to its booming stage, was by Bostonian Frederic Tudor (1783-1864) also known as the “Ice King.” Tudor was the right man at the right time to kick-start the ice harvesting industry. He was born of a wealthy Boston lawyer and could afford to accrue the initial losses that were certain to come from a new venture.

On a visit to the Caribbean – it’s not known if it was for business or pleasure – he got the bright idea to bring ice to the tropical isles. There was certainly a need for it. He thought back to the many ice ponds back home. In 1806 at the age of 23, he utilized his brig Favorite to take ice from his father’s pond in Saugus, to Martinique. For four years, Tudor was in the red and did not turn a profit. In 1810 he made his first profit and the ice industry began to pick up steam.

Within a few short years he would add Cuba and a number of southern states. As technology advanced and he learned to preserve and cut better, he expanded into Europe and even India and was estimated to be worth $220 million in today’s money. People loved his “crystal blocks of Yankee coldness.”

Ice harvesting was a pretty darn dangerous business from harvesting to icebox. Men would venture out onto frozen ponds with saws, gaffs, tongs and picks and methodically cut and drag blocks. Falling into the water was dangerous enough, but the sharp tools were responsible for the majority of the injuries. Manipulating these heavy blocks of ice came with its own hazards, as did shipping them.

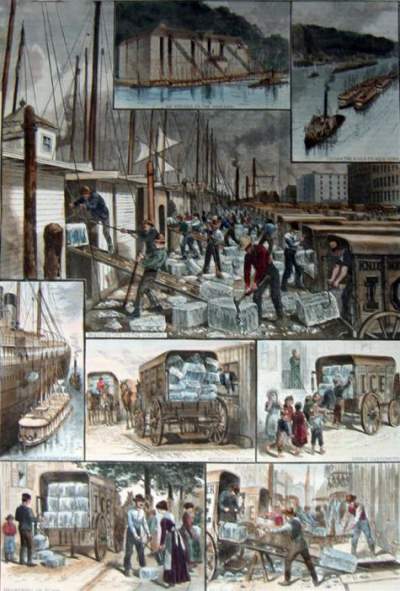

Collage of ice harvesting activities. (Harper’s Weekly)

The process of harvesting, would take dozens of men up to a month. First they would scrape all the snow, leaves and debris off the top. The men would then score a large section called a cutting grid. The cutting grid encompassed that day’s section to be harvested. Then, further score marks of smaller sections would be made and these were called “rafts.” These were rows that ran the length of the cutting grid.

The men would then cut into the rafts of two feet thick ice and pull the ice cakes out, often with the help of horses. A typical ice cake would be 22″ x 32″ to 44″. These were then pulled along with gaffs and floated to the pond’s edge.

These ice cakes, would then go up a chute into the nearby storehouse where more men were waiting to cut them into even smaller sections, depending on existing or expected orders. While the waited delivery the ice cakes would be insulated with saw dust and/or hay.

As you can see, a lot of work (and danger) went into bringing ice to iceboxes in homes across America. One could genuinely appreciate that “simple” ice cake that was brought to your home. I’d imagine that the average person was quite aware of the harvesting process in that day. If they didn’t appreciate because of the labor and risk, the expense of the product and delivery would certainly grab you.

Of course, the cost would go down as the demand went up and technology made the harvesting safer and easier. Today the entire industry has virtually been replaced with the refrigerator. I say, virtually and not entirely, since ice harvesting still takes place in a few areas of the world. In isolated parts of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire and parts of Canada the ice harvest is a communal event.

The precursor to the refrigerator, the icebox is something that my Nonno and even my mom recalled as a child growing up in the 1950s. Certainly there are some readers that recall using an icebox. We would love to hear your stories!

Refrigeration is a modern convenience that we just can’t live without and certainly one that I take for granted…or took for granted until I wrote this! Now when I go to my refrigerator, I think of Frederic Tudor’s foresight and the thousands of unnamed men who harvested the ice and started an industry.

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA